Book Review: Ten Thousand Crossroads: The Path as I Remember It

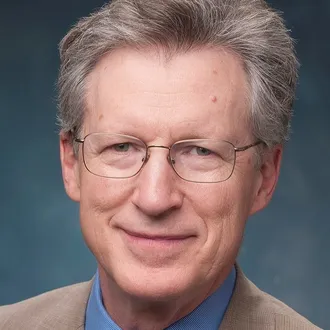

Reflecting on Balfour Mount’s autobiography, “Ten Thousand Crossroads: The Path as I Remember It”, our colleague and longtime palliative care leader, Robert Fine, MD, wrote a personal response, drawing on what connected him to the story. Dr. Fine feels that it is important to understand the roots of our field—experiencing the evolution so that we know where we came from. Balfour Mount, MD, OC, OQ, a Canadian cancer surgeon at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal, is the founding father of our field. He coined the term “palliative care”, recognizing and addressing the needs of the whole person and those who care for that person.

Fine’s review makes clear that the early leaders in the field were largely focused on care at the very end of life—care of the dying. In the 50 years since, the field has evolved to address suffering during any serious illness, independent of prognosis. We now take care of people with long-term chronic illnesses (like heart failure, end stage renal disease, or dementia), which people may live with for many years. And we take care of people who may be cured (such as those receiving a bone marrow transplant for acute leukemia and other blood disorders), and people living with progressive illness that is not responding to treatment. Today, palliative care is defined as specialized medical care for people living with a serious illness, focused on providing relief from the symptoms and stress of a serious illness. The goal is to improve quality of life for both the patient and family, and it can be provided at any age and any stage of any serious illness.

To know who we are as a field, we have to know where we came from. In addition to reading Cicely Saunders and Elisabeth Kubler Ross, Balfour Mount’s book is an essential piece of our history.

Dr. Robert Fine's Review

In my opinion, all palliative care professionals should have a reasonable knowledge of the founders and founding years of our specialty. Too few of today's practitioners truly understand the challenges faced, the price paid, or the origin of the insights developed. The book, “Ten Thousand Crossroads: The Path as I Remember It”, takes the reader on a journey of incredible breadth wonderfully laden with sorrow, humor, and hard-won wisdom.

The book begins with the words “as a toddler...” and I will confess a brief moment of hesitation before learning in the first chapter of Mount’s early death anxiety in second grade, followed by witnessing a death several years later when making a house call with his physician father. These reflections on the roots of his later professional work caused me to compare his early life experiences with my own. I suspect many readers in our field will ponder the same. What was it about our youth that later guided us into the profession of medicine, nursing, social work, or pastoral care, and then subsequently to focus on the experiences of our patients confronting the realities of life with a serious illness?

"In my opinion, all palliative care professionals should have a reasonable knowledge of the founders and founding years of our specialty."

Dr. Mount went on from medical school to become a practicing academic urologist at McGill University. As he matured in his practice, and gained experience with many patients, he was able to focus professionally on the creation of our field. On his journey, he relates his interactions with family, colleagues, and patients (his best teachers), as well as his relationships with the likes of Cecily Saunders, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, Viktor Frankl, and the Dalai Lama.

As one might imagine in a book of 590 pages, there is simply a wealth of remembrance. But the purpose of a review is not to comment on every historical detail. One particular theme emerged for me at different points in his story, which will be the theme I comment on to close this review. This has to do with the interaction of the spiritual with the medical in our interdisciplinary field. Along with sharing his childhood anxiety about death, his professional experiences with his patients, and his personal brushes with mortality (by airplane crash and cancer), Dr. Mount shares his first exposure to “medical prayer” and faith. He goes on to reflect on the accumulation of medical wisdom noting that it is “never linear.” Dr. Mount writes, “It (medical wisdom) more closely resembles the drawing together of an elegant, infinitely complex, woven fabric. Working with countless information strands of all colors, textures, strengths, and degrees of relevance, one moves toward an imagined seamless whole that, if you set your sights high enough- that is to say, on the suffering of the whole person rather than simply the disease- is never quite realized.”

"The type of palliative care he laid the foundation for and so many have built upon is spiritually grounded on questions of meaning, purpose, and human relationships."

This is one of the few passages that perplexed me. My professional journey has taught me that well-practiced interdisciplinary palliative care in our hospitals, clinics, and homes as Dr. Mount championed, taking into account the full tapestry of elements that make up the human experience, creates in us and delivers to the patients and families we serve essential wisdom, even in the face of suffering. In my view, eventually for each person, mortality is not a medical problem to be solved, rather it is a spiritual and existential challenge to be faced. Dr. Mount recognized the importance of attending to the spiritual journey of patient, family, and professional in a manner that none of my teachers during medical school, nor residency, did. The type of palliative care he laid the foundation for and so many have built upon is spiritually grounded on questions of meaning, purpose, and human relationships. It recognizes the wisdom of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, “We are not human beings having a spiritual experience. We are spiritual beings having a human experience.”

Upon reading the path of Dr. Mount’s life as he remembers it, he is surely a spiritual being who has helped us all, patients and professionals alike, better apprehend the human experience of life and particularly life in the face of serious illness.