How to Reduce Risk for Older Adults with Age-Friendly Care

It happens all too often. An older adult goes to their primary care clinician for medical clearance for a knee replacement. With multiple comorbidities, mild cognitive impairment, and a long medication list, they feel relatively healthy, but experience a lot of pain when walking, and want to move forward with the procedure. The clinician clears the patient for surgery. After the knee replacement, the patient begins to heal, but develops complications from delirium and is moved to a skilled nursing facility for rehabilitation. Unfortunately, the patient never regains enough cognitive and physical function to return home – and neither the clinician who cleared him for surgery, nor the orthopedist, learn what happened.

Several misconceptions play into poor outcomes like this one.

Myth #1: Geriatric patients are frail and at risk for poor outcomes – that’s just the way it is and there’s nothing that can be done about it.

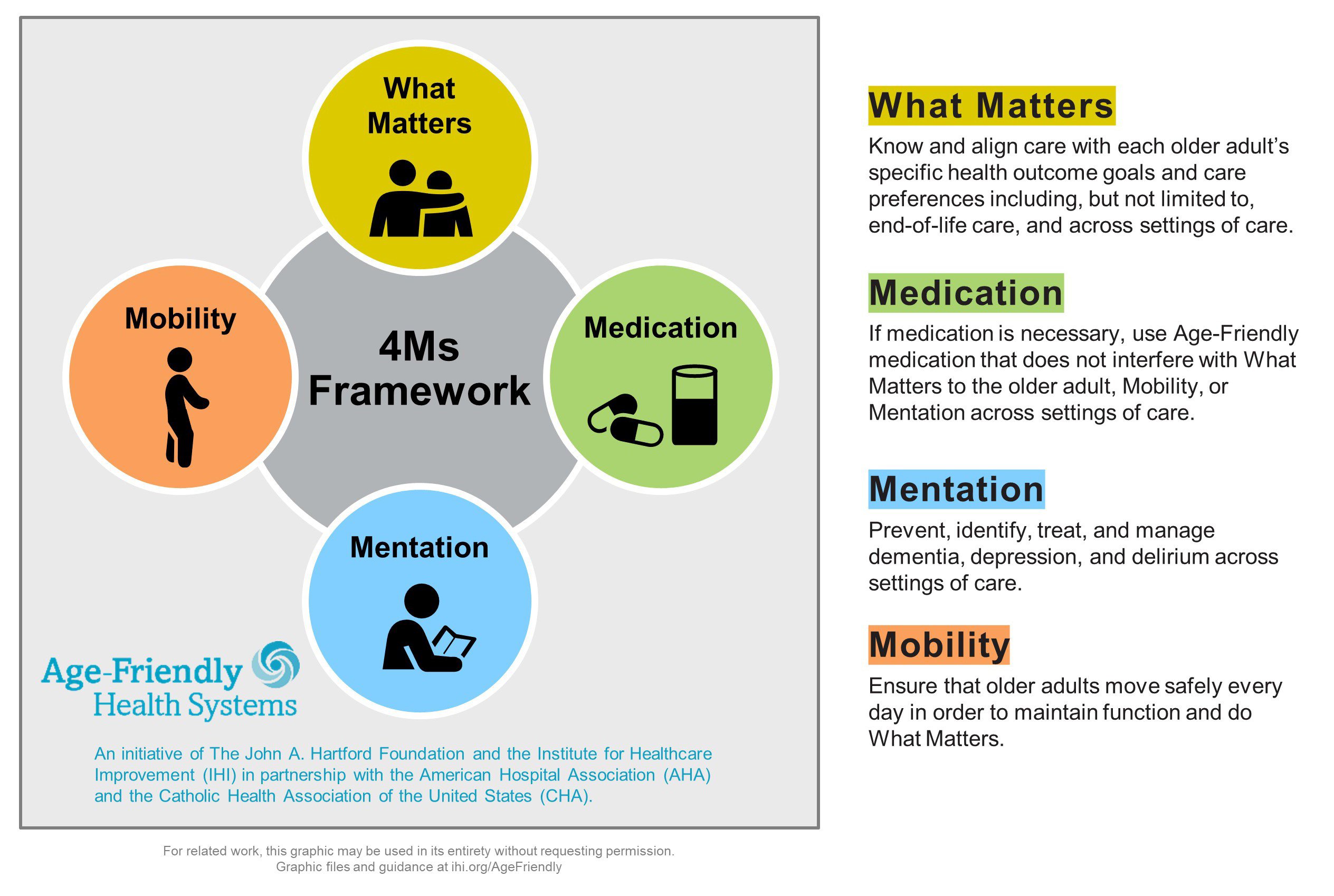

Reality: Clinicians can reduce common risks for older adults and provide care that aligns with patients’ goals and preferences. That’s where the Age-Friendly Health Systems framework comes in, which “aims to follow an essential set of evidence-based practices; cause no harm; and align with What Matters to the older adult and their family caregivers”. It has been adopted by more than 800 sites of care across the US, and incorporates these foundational principles of age-friendly practice, known as the 4Ms:

- What Matters: Know and align care with each older adult’s specific health outcome goals and care preferences including, but not limited to, end-of-life care, and across settings of care

- Mentation: Prevent, identify, treat, and manage depression, dementia, and delirium across settings of care

- Mobility: Ensure that each older adult moves safely every day to maintain function so they can return to doing what Matters

- Medication: If medication is necessary, use age-friendly medications that do not worsen mental status and function, and do not interfere with What Matters to the older adult, with their continued Mobility, and their level of cognition and Mentation across settings of care

"The 4Ms evidence-based framework has demonstrated impact on outcomes that matter to older adults and to health systems — patient satisfaction, length of stay, incidence of delirium."

Myth #2: Common surgical procedures, such as a knee replacement, present little risk of harm for the older adult.

Reality: Older adults are at a higher risk for bad outcomes for the same procedures that are relatively low-risk for younger adults. For example, age and an increased Charlson comorbidity index have been found to increase the rate of discharge to an extended care facility after a knee replacement by 40% [1].

Myth #3: When treating the older adult patient, survival is the always the highest priority.

Reality: A majority of older adults would forego treatment if there were a high probability of functional (74%) or cognitive (89%) impairment (this is true even if the treatment burden would be low). For many older adults, spending the rest of their lives in a nursing home is a fate worse than death, yet we rarely warn our patients of the probability of that outcome, nor do we do everything in our power to keep that from happening [2].

The reality is that what most hospitals consider to be a successful surgical outcome based on existing quality measures – a surgery and subsequent hospitalization with no infection or fall, and discharge alive to a skilled nursing facility – is quite different from what most patients would define as a successful outcome, which is independent living in their own homes. These differences in perceived “successful outcomes” are outlined below, further illustrating the gap. Additionally, CAPC’s new course, Reducing Risks for Older Adults, is meant to call attention to and hopefully narrow, this gap.

| Patient’s Perspective: Failure | Hospital Quality Measures: Success |

|---|---|

| Placed in a nursing home for long-term care | Successful surgical outcome |

| No longer able to function | Discharged alive to nursing facility |

| Unable to be with loved ones at home | No post-operative infection or fall |

“When the discussion with the older adult and their family begins with What Matters, the care team moves away from assumptions, and can plan for the care and outcomes the older adult wants."

Myth #4: Delirium is a common and minor side effect of surgery and hospitalization in older adults.

Reality: Delirium, often casually referred to ‘confusion,’ ‘disorientation’, or being ‘out of it’, is an abrupt and fluctuating alteration in level of consciousness, attention, cognition, and either slowed or agitated motor function. Its cardinal symptom is inattention, the inability to focus or maintain focus. Common among older adults, delirium is typically a consequence of medical illness like infection or drug side effects. It is especially common in response to stress in people with even a very mild pre-existing cognitive or brain dysfunction, or frailty. Occurrence of delirium is associated with serious adverse outcomes for patients.

Once thought to be a passing symptom without long-term consequences, we now understand that preventing delirium is of the highest importance. Failure to recognize and act on this reality leads to the fact that delirium is present at discharge among 32-60% of hospitalized older adults [3]. Persons with hospital-associated delirium:

- Are 4.5x more likely to be institutionalized, and 2x more likely to be readmitted to the hospital [4]

- Are 12x more likely to be diagnosed with dementia over the next 4 years [5]

- Experience greater decline in activities of daily living (ADLs) after a surgery [6]

- Have higher 24-36 month post-operative mortality; mortality rates following an episode of hospital-induced delirium are approximately 30% at three months, and 80% at three years [7]

Myth #5: There is nothing I can do to prevent my older adult patient’s risk of developing delirium.

Reality: Prevention is key! While delirium can develop in any context or care setting, surgery and other high-risk interventions are known and powerful precipitants for the older adult patient.

The good news? Clinicians can take steps to assess for and reduce risks of delirium!

How to Assess for and Reduce Risks of Delirium

CAPC recommends following the below five strategies.

1. Systematize your approach to risk prevention

The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) is a program for systematically preventing delirium for older adults in the hospital. HELP provides clinicians with online interactive training in how to implement the program, and has been shown in several studies to prevent many adverse outcomes of hospitalization.

2. Train clinicians

Take CAPC’s new course, Reducing Risks for Older Adults, and use the learnings to educate physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, and discharge planners about the importance of delirium prevention, including how to prevent it. This course has practical clinical guidance on how to:

- Incorporate the 4Ms into patient care; first, download the Guide to Using the 4Ms in the Care of Older Adults to learn about the 4Ms Framework and how to become an Age-Friendly Health System

- Identify older adult patients who are at risk for poor outcomes before they happen

- Reduce the chances that a patient develops delirium by reducing pharmacological, medical, and environmental risk factors both before and after surgery

- Help patients and caregivers understand the long-term impacts that surgery and hospitalization can have on future quality of life – especially the odds of ending up in a nursing home (long term), and to incorporate this information into care planning, and decision-making

Like other CAPC courses, completion of this new course provides free continuing education credits for physicians, nurses, social workers, case managers, and licensed professional counselors at member organizations. Additionally, free MOC (Maintenance of Certification) points are available for ABIM-boarded physicians.

3. Implement screening

Despite being the most common side effect of hospitalization for older adults, delirium often goes undiagnosed or misdiagnosed. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) is an evidence-based tool for non-psychiatrically trained clinicians. CAM is used to identify and recognize delirium quickly and accurately in clinical and research settings.

4. Make palliative care part of the plan

Pre-operative palliative care consultation has been shown to reduce an older patient’s 180-day mortality by 33% [8]. Implement a trigger for palliative care assessment for high-risk geriatric patients contemplating surgery. Who is high risk? People over the age of 70, who have any level of memory loss, frailty, diabetes, hypertension, multi-morbidity, a high anticholinergic drug burden.

5. Assess for and reduce or eliminate deliriogenic drugs

Many commonly used medications including SSRIs, antihypertensives, diuretics, and over-the-counter sleep aids are potent anticholinergic agents, and markedly increase risk of delirium. Discontinue or reduce these agents prior to surgery [9].

Endnotes

-

Schwarzkopf R, Ho J, Quinn JR, Snir N, Mukamel D. Factors Influencing Discharge Destination After Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Database Analysis. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2016;7(2):95-99. doi:10.1177/2151458516645635

-

Terri R Fried MD, et al, Understanding the Treatment Preferences of Seriously Ill Patients, NEJM 2002; 346: 1061-66

-

Marcantonio ER. Delirium in Hospitalized Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 12;377(15):1456-1466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1605501. PMID: 29020579; PMCID: PMC5706782.

-

George, James, et al, Causes and Prognosis of Delirium in Elderly Patients Admitted to a District General Hospital, Age and Ageing 1997; 26: 423-27

-

Witlox J. Delirium in Elderly Patients and the Risk of Postdischarge Mortality, Institutionalization, and Dementia. JAMA. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/186304. Published July 28, 2010. Accessed March 3, 2020.

-

Marcantonio, Edward, MD, SM, et al, Delirium Is Independently Associated with Poor Functional Recovery After Hip Fracture, JAGS, 2000; 48(6)

-

Rockwood, K et al, The risk of dementia and death after delirium, Age Aging 1999, 28:551-556

-

Ernst, KF, et al, Surgical Palliative Care Consultations Over Time in Relationship to System wide Frailty Screening, 2014 JAMA Surg, 1121-1126.

-

Croke L. Beers Criteria for Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Patients: An Update from the AGS. Am Fam Physician. 2020 Jan 1;101(1):56-57.