How to Address Vaccine Hesitancy for Patients Living with Serious Illness

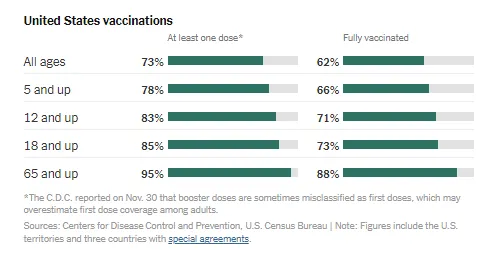

Almost two years ago, the U.S. declared a public health emergency, and within just nine months, the first vaccine was approved for emergency use. As of December 29, 2021, 205 million people in the United States have been fully vaccinated (62% of the population). Additionally, 67.3 million people have received a booster dose.

With Delta and Omicron surging throughout the country, vaccines are proving to be critical at preventing serious illness, reducing hospitalization rates and death among the vaccinated. Even though serious illness and death is far greater for the unvaccinated, the reasons for people resisting vaccination vary, and are personal and complex.

While it is not our job to change minds, clinicians have an ethical responsibility to provide accurate information about the available vaccines, which are safe and proving to save lives. This does not mean that we should judge or talk people into making decisions. But we should offer facts, to help people learn how protective the vaccine is and answer questions.

Vaccine Hesitancy

A new study illustrates common reasons people choose to be unvaccinated, including: perception of risks of vaccines (e.g., blood clots); risks of the vaccines (e.g., length of time for vaccine development); lack of trust in institutions (e.g., distrust in government); perception of the benefit (e.g., not believing COVID-19 poses considerable risk to them); and more.

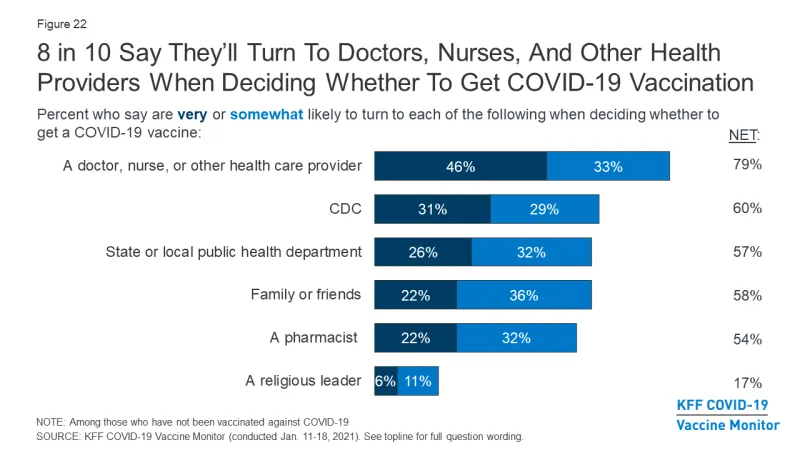

There is a bright light: survey data shows that the majority of adults will turn to their doctors, nurses, and other health care providers, when making decisions about the COVID-19 vaccine. We have an important role to play in helping this pandemic come to an end.

Figure 1: Survey data shows that 8 in 10 people will turn to health care providers when making a decision about the COVID vaccine

Palliative Care Clinicians Have a Unique Opportunity

The patients that palliative care clinicians care for, those living with serious illness, are among the most at risk for severe COVID outcomes. After all, they are already living with serious illness, and would have less ability to recover if they did get a severe case of COVID. Those with a serious illness have a strong medical indication for COVID vaccination.

"We palliative care clinicians have a secret weapon: in many cases, we have already earned the trust of our patients."

We palliative care clinicians have a secret weapon: in many cases, we have already earned the trust of our patients and their families. We’ve been talking to them about what matters, how to manage their illness, and how to cope with tough situations. When we speak with them about the COVID vaccine, we already have a track record of trust. Our patients know what we can do and what we care about—namely, them. So palliative care clinicians have a unique opportunity to address vaccine hesitancy. Given the public health emergency, and the vulnerability of our patients, we must use our voices to help them protect themselves—and their families.

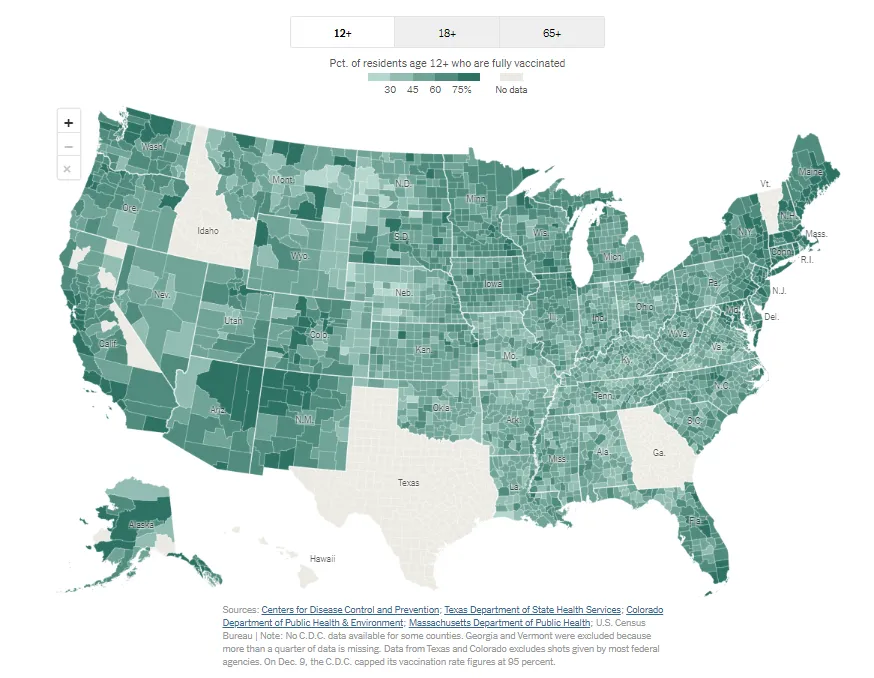

As mentioned earlier, 62% of people eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccination (>5+ years old) are fully vaccinated (see Figure 2). With the Delta and Omicron variants raging throughout the U.S., there is still a lot of work to be done. As clinicians, we can do our part by offering our patients, and their families, information through respectful dialogue. The hope is to help more people move forward and make a plan for inoculation.

Figure 2: The New York Times reports state-by-state vaccinations

As clinicians, we can guide our patients, and their loved ones, to receive the vaccine (in full), and answer any questions they may have. We can model, by receiving the vaccine ourselves, or point out public figures that they may look up to, who have received the vaccine. We can provide our patients with data, which they may normally not have access to, or help them dispel misinformation learned online. We have the unique opportunity to connect with our patients based on the level of trust we develop with them; we can build on this relationship by acknowledging and talking with them about vaccine hesitancy.

"We have the unique opportunity to connect with our patients based on the level of trust we develop with them; we can build on this relationship by acknowledging and talking with them about vaccine hesitancy."

How to Have the Conversation

In an effort to help clinicians with these conversations, my team at VitalTalk developed a conversation guide, which was adapted from motivational interviewing and research on vaccine hesitancy. The approach outlined in the guide gives clinicians the opportunity to engage with patients on a 1-on-1 level, as people, so that their individual concerns have space to be said out loud, and talked over.

The guide is an evidence-based roadmap for a sometimes-tricky conversation with patients—and their family members or other people who matter to them. It is meant for you as a clinician to reference—before having a vaccine conversation. Here’s how we recommend having the conversation, with more detail in the guide itself:

1) Start with Open-Ended Questions

When meeting with your patient, do not assume vaccine acceptance—instead, a soft start into a controversial topic may enable engagement. See below for an example:

Patient says: All people are talking about lately is the COVID vaccine and Delta/Omicron. I’m just so over this. What are your thoughts about the vaccine?

Clinician says: I understand—this has been going on for a long time. What have you been hearing? I’d be interested in how you see the positives and negatives with the vaccine. (Read more.)

2) Acknowledge Patient Concerns without Judging

Displaying empathy reduces the perception that you approve or disapprove of someone. It’s important to acknowledge a patient’s concern without showing judgement. An example of this dialogue is included below:

Patient says: I just don’t trust vaccines, especially this one.

Clinician says: I have heard other people say they are worried about the vaccine. Could you say more about your concern? (Read more.)

3) Avoid Criticizing the Patient’s Information Sources

Instead of showing skepticism or criticizing what the patient is telling you, cite your experience and/or point the patient to high-quality sources they may be more likely to trust, from a positive frame. This reinforces the principle of not arguing against misinformation, but instead, providing high-quality information from a positive frame. Here’s an example of this in action:

Patient says: You just never know what the side effects will be.

Clinician says: Yes, it is true that there have been some side effects. The most common side effect is some soreness at the injection site […] (Read the rest of this response and other examples.)

Patient says: I don’t want my DNA changed by this vaccine. That scares me.

Clinician says: I can understand why that would sound scary. The COVID-19 vaccines approved for use cannot change or interact with your DNA in any way. Instead, mRNA acts as a messenger, which delivers instructions (genetic material) to our cells, to start building protection against virus that causes COVID-19. This does not enter the part of the cell where our DNA is kept (the nucleus), so there is luckily no way that your DNA can be altered. (Read the rest of this response and other examples.)

4) Show Awareness of Your Status as a Messenger

This is especially important for people of color and members of other underserved groups. This recommendation reinforces that as a clinician, who you are as a messenger matters. And the quality of your prior interactions with that patient contribute to your authenticity and trustworthiness. During your conversation, you can talk about how you and your patient have made other important medical decisions, and you can cite stories (without identifying data) about other patients like them. For instance:

Patient says: I am not sure that the needs of my people have been taken into account.

Clinician says: I realize that the medical system in the United States has not treated everyone fairly in the past, and that it has been racist. I recognize the injustices that have happened in the past and are still happening now. The COVID vaccine was tested in thousands of people, about 10% of whom are people of color. There were no differences in side effects and the benefit—a 95% reduction in risk of serious infection or death from COVID was the same in all racial groups. We are handling the COVID vaccine better […] (Read the rest of this response and other examples.)

5) Link Vaccine Acceptance to the Patient’s Hopes and Goals

As palliative care clinicians, we regularly discuss goals with patients and families. Let this tip be part of that picture, as it may show how the vaccine is a stepping-stone towards a future the patient wants–staying as healthy as possible–ultimately motivating them, or moving them toward acceptance.

Patient says: I’m just going to wait. I haven’t gotten COVID yet.

Clinician says: Of course, this is your decision. I do think that the vaccine will reduce your chances of getting a bad case of COVID, especially with the Delta and Omicron variants, and it is a step towards normal—a social life with fewer restrictions […] (Read the rest of this response and other examples.)

Final Thoughts

This guide is meant to help respond to patient concerns, but does not include the standard back-and-forth that good communication requires. Please keep in mind that when patients are reticent to voice their concerns, it is better to suggest a topic and ask permission to talk about it and explain what you know, vs. lecture.

Keep in mind that the earlier-mentioned research on vaccine hesitancy shows that people holding extreme negative views on vaccines are unlikely to be swayed. Thus the approach outlined in the guide is designed to address people who are indeterminate, unsure, or are in the process of deciding about their feelings regarding vaccines. For this group, openness, empathy, and the offering of information after they give permission or show interest can enhance trust and your credibility as a messenger.

Edited by Melissa Baron. Clinical review by Andrew Esch, MD, MBA.