Learning about Palliative Care in India, While Waitlisted for Nursing School

The first home visit of my career occurred in rural Kerala, India, during the University of Iowa’s India Winterim Pain and Palliative Care course at Pallium India—a life-changing, three-week, field-based program. This course provided me with an opportunity to learn within India’s diverse cultural, socioeconomic, and geographical mosaic, while simultaneously kickstarting my nursing career. It included home visits with the Pallium India team, as well as on-site teaching and service projects (e.g., a health fair for Pallium staff, methadone initiative, public awareness of palliative care in schools, autonomic dysreflexia education and interventions, a “Sans Pain” project, and various cultural events). The home visits were not only a privilege, but also the highlight of my time abroad.

As I walked into the home with the Pallium India team, I met an eighteen-year-old, who had fallen from a terrace when she was twelve and was left paralyzed. Bags of medication hung from the bedposts. Mirrors were positioned around her so that she could see herself. I could not imagine having an accident reduce my universe to a hot and dusty 7’x7’ bedroom. While I do not speak Malayalam (the Dravidian language spoken in Kerala), I listened and watched the body language around me, while medicine reconciliation took place and her father shared information about the past week.

The Pallium staff then provided consultation, education, support, and potential follow-up times for this family, which was customary for all community members who receive home visits. Shortly after leaving the patient's home, the nurse translated the conversations. Though I did not speak Malayalam, I had understood the weight of it all, through the family's body language and facial expressions. I remember thinking how impactful it was to be able to comprehend a scenario without a shared language.

India: How Did I Get There?

While awaiting admission to the University of Iowa’s College of Nursing, I learned about M. R. Rajagopal (Dr. Raj), a Pallium India physician who was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize (2018) for his work addressing suffering and opioid availability in India. A group of nursing students spoke to our undergraduate class about their experience working with him, and I knew in that moment that I needed to meet him and see his work firsthand. And luckily my school had a program that would accommodate it.

That summer, I was waitlisted for nursing school, but had been accepted to join the India Winterim Course (mentioned earlier). With less than a month until the start of the semester, I decided to embark on a trip that would truly inspire the rest of my career.

I began my journey from Iowa to India, hoping for cultural immersion and learning with the innovative Pallium India in Vattapara, Kerala. Upon landing in Abu Dhabi for our connecting flight, I received an email from the College of Nursing. The subject line read, “ADMITTED into Iowa’s December 2020 nursing cohort!” Halfway across the world, I received the news I had been hoping for. I could not help but think there was a reason it happened this way.

"Halfway across the world, I received the news I had been hoping for. I could not help but think there was a reason it happened this way."

Meeting Dr. Rajagopal

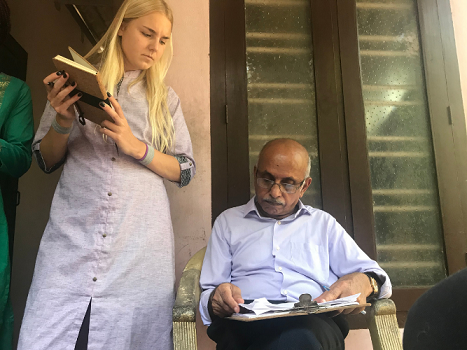

Dr. Raj met with our group soon after we arrived, and explained the mission of Pallium India: to reduce serious health-related suffering. Through my jet lag fog, I listened as he challenged us to think about what “health care” really meant.

As he described palliative care, I was not surprised. Treating the patient holistically, rather than just their disease—shouldn’t that be the standard of health care? If this is not the approach taken in America, what does this palliative approach look like in action? Are we being short-changed in America?

"Treating the patient holistically, rather than just their disease—shouldn’t that be the standard of health care?"

Dr. Raj further explained his goal of reducing health care-related suffering throughout one’s life. Accidents, poor prognoses, and chronic illness do not discriminate against age groups. It was clear to me that Dr. Raj’s definition of health care encompasses advocacy and comfort for those living with any injury or disease, at any stage of life. He aims to meet the individual’s personal health wishes and life goals rather than ‘cookie cutter’, idealistic patient outcomes.

I jotted down as much as I could in my little brown notebook… “The most fundamental principle of medicine is love. - Paracelsus”... “Care beyond cure”. There was so much I had yet to discover.

Observing Care Through a Different Lens

The unique opportunities provided by the home visits to Pallium patients gave insight into the harsh differences of our health care systems. I quickly learned that there is no equivalent of HIPAA in India—there no patient rights or privacy. We could read the patients’ charts, wherever and with whomever. Pallium India volunteers took photos of patients with simple verbal permission. The Pallium India nurses had to prioritize when to use gloves.

That night, my journal overflowed with aspects that were mundane to most, but eye-opening and unforeseen to me. This clinical setting was far from what I had experienced as a nursing assistant. I felt guilty for all that I had taken for granted in the states: fully stocked boxes of gloves in various sizes; state of the art health care institutions with the latest technology; rolled eyes at hand hygiene audits.

The variance in supplies and standards were not due to a knowledge deficit, rather a lack of availability of PPE, and no governing body to set guidelines for proper safety practices. Despite the lack of these standards, Pallium nurses set the standard for what sacrifice truly means. Each day they put their own lives at risk for their community, dealing with the circumstances in front of them, proud of the care they could provide. I am humbled to have had the opportunity to work beside them.

An Inspiring Home Visit

Another home visit that I will forever remember was with a 60-year-old woman with Creutzfeldt-Jakob’s Disease. Despite the devastation of the diagnosis, the visit wholesomely inspired me. The woman’s caregiver was her daughter, a trained RN, who had given up everything to take proper care of her mother (all day, every day). This care was intricate and precise; all of the mother’s necessary activities of daily living were made possible because of her daughter. The pillows were neatly tucked under perfectly positioned elbows and heels, preventing pressure ulcers from immobility. Not a crumb or stain could be found on her saree, nor on the blanket keeping her warm. Her face was washed, skin moisturized, and the room smelled fresh from the breeze brought in through the deliberately cracked window. The home was clean and organized, and the room she rested in contained supplies for her care regimen. There were also photographs of family members, and a small couch where the daughter slept every night, tending to her mother’s every need.

The intentionality of the daughter’s work was a visual representation of the love and respect she felt toward her mother. I aspire to be that compassionate for each of my patients—at the end of the day, a patient is always someone’s family member. The daughter shared their challenges and frustration with hospitals in the area. She felt dismissed, saying that if the doctors could not cure the illness, they did not want to deal with the case. For me, this highlights the need for palliative care. She was not demanding a cure; she simply wanted more time with her mother. To this day, tears accompany the memory of the moments spent in their home.

My Other Work in India

Aside from home visits, we worked on projects brainstormed by the Pallium India staff. Upon request, my group of three created guidelines for the Pallium nurses and physicians to seek out eligible patients for methadone. This enabled the nurses to identify key parameters within these patients and suggest methadone use to the prescribing physicians. Luckily, I worked alongside two pharmacy students who guided our project. Methadone for pain had been legal in India for a year but the complex drug interactions were intimidating, ultimately limiting its use. However, it is the only affordable long-acting opioid in India.

This project helped me to understand adverse drug reactions and the effects of pain medication prior to starting my formal nursing education. By the end, we compiled a checklist for the nurses to use when screening patients for possible methadone use. We completed our project with the hope that our contributions would have a lasting impact for Pallium India.

The Humanity of Nursing

This trip made known to me the humanity in which the field of nursing is rooted. This common ground connects nurses everywhere. Every nurse, no matter the setting, has the distinctive role of providing both medical and emotional individualized care to their community. I feel that I was meant to begin my nursing education in India, so that the foundation of my career would be built upon the principles of Pallium India and their strong advocacy to reduce pain and suffering.

Two years later, my work as a nursing student is complete, but my work as a nurse is just beginning. I often reflect on my experience in India. Coincidentally, I accepted my first nursing job on a neuroscience and spine unit, which allows me to keep the memories of my first home visit near and dear to my heart. To the nurses of Pallium India, I am so grateful to be following in your footsteps, down the very road you have paved for me along with other future nurses. Your advocacy and passion are unmatched. I will forever strive to emulate the dedication, kindness, and compassion of Dr. Raj.

Takeaways from My Time in India

My time at Pallium India has shaped me into the nurse that I am today. As a way of giving back to the many health care workers who have shared their learnings with me, I wish to share mine with you.

1) Our patients are not their disease

It is a privilege to work with people and families at their most vulnerable, and acknowledging this includes allowing their voices to be heard. As nurses, we do not treat diseases, injuries, and ailments; we treat our patients. Be a light for every patient you work with.

2) There is much to learn from other cultures and countries

I am incredibly fortunate for the time I spent abroad, as I gained immeasurable perspective in doing so. The emphasis on family that I witnessed in Trivandrum was grounding, heartwarming, and inspiring. It serves as a reminder to look after loved ones, in sickness and in health.

3) Palliative care core values are applicable to all types of care

Although I am not a palliative care nurse, I incorporate its principles into much of the care that I provide. Nonpharmacologic interventions for pain, repositioning patients every two hours, and the various other creative ways in which nurses comfort a patient during a shift are branches of the tree that is palliative care.

A note of gratitude:

I wish to express my gratitude to the volunteers of Pallium India here in the US, especially Dr. Ann Broderick ("Dr. Ann"), for her encouragement to write and publish this narrative. Dr. Ann, your continued mentorship during my time at Pallium India and throughout nursing school are appreciated more than you will ever know!