Let’s Stay on Message with Palliative Care

In 2011 and again in 2019, CAPC audience research showed that the public doesn’t understand what palliative care is, often confusing it with end-of-life care and hospice. Other studies have shown the same. And, focus groups among physicians have shown that while they do understand what palliative care is, their inclination is still to refer patients to palliative care only at the end of life.

In 2024 and 2025, palliative care professionals told CAPC through our annual Palliative Pulse survey that one of their top concerns is misconceptions about what palliative care is and isn’t. It’s not just one group that misunderstands: it’s organizational leadership, potential referring providers, and patients and families. One respondent noted, “…having to justify the need for palliative care to colleagues—convincing staff that palliative care isn’t just end-of-life care, hearing that ‘the family isn’t ready’ or ‘they’re not dying right now’.”

So, what can palliative care clinicians do to overcome these misconceptions?

Communicating About Palliative Care

While challenging, the most essential strategy is message discipline—using consistent language and concepts about palliative care’s beneficial impact on quality of life for anyone living with a serious illness. But we can do this only by avoiding language that conveys mixed messages. This may seem like a small intervention, but it is extremely high-yield.

How we describe palliative care in our public messaging may seem accurate and clear to those of us in the field, but we are not talking to ourselves. We are speaking to our audience. What matters is what resonates with them. Imagine if you were the CEO of a hospital or health system, a provider, a patient, or a family member. If you heard palliative care clinicians talk about death and dying, and that’s what you read on every palliative care website, your takeaway would be that palliative care is only for those at the end of life.

"If we ourselves aren’t clear in describing what we do, how can our referral sources correctly identify the patients who need our care?"

If we ourselves aren’t clear in describing what we do, how can our referral sources correctly identify the patients who need our care? How can the public understand and know what to ask for when facing a serious illness? It will take all of us to shift perceptions and change an ingrained, but incorrect, narrative that palliative care is synonymous with end-of-life care.

Market research instead tells us the public wants an extra layer of support that improves their quality of life while they are receiving all other treatments for their disease. They want a specialized team that works together with their other doctors, and they want to be part of that team. Using these five user-friendly messaging principles when communicating to the public about palliative care is key:

- Talk up the benefits

- Present choices at every step

- User positive stories

- Invite dialogue, and not just once

- Invoke a new team

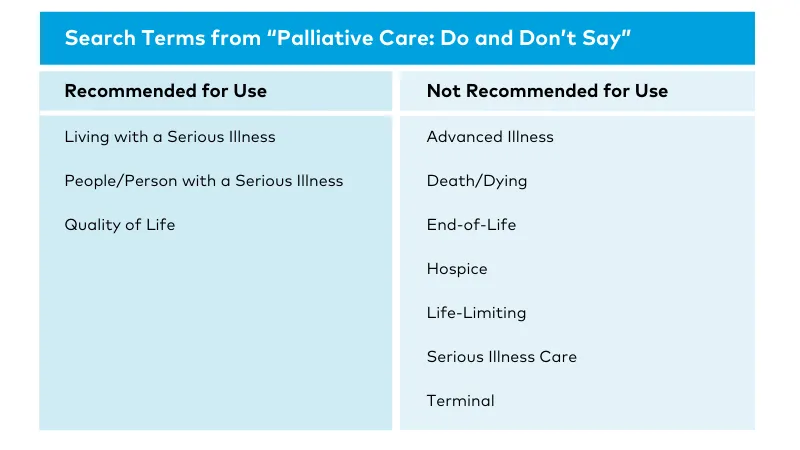

As an analysis conducted in 2022 by CAPC’s Rachael Heitner, MPH, shows, messaging reliance on end-of-life language may instead be the norm. In the qualitative review, 48 palliative care program websites were searched for words or phrases included in CAPC’s messaging resource, Palliative Care: Do and Don’t Say, a reference for what to say, or avoid saying, when discussing palliative care. The recommendations on this reference are drawn from common English end-of-life terms as well as CAPC’s audience research.

We included palliative care program websites run by three different types of organizations: hospitals (n=16), hospices (n=16), and other community organizations, like home health agencies (n=16).

What Does Research Show Us About Messaging?

Terms and Phrases Not Recommended

For this analysis, “hospice” was not counted if it appeared in the name of the organization. With this caveat, it was still the term not recommended for use that appeared most often—at least once on half of all included websites. This was followed by “end of life” (25%), “life-limiting” (25%), “advanced illness” (21%), and “terminal” (15%). The rest of the terms not recommended for use (e.g., “the seriously ill”) appeared on less than 10% of included websites.

“Hospice” was used when describing palliative care most often by hospice organizations (63%), compared to hospitals or other community organizations (44% of each). Hospice organizations also used “life-limiting,” “advanced illness,” and “terminal” more than the other types of organizations. This, of course, makes sense if you are promoting hospice rather than palliative care services.

Recommended Terms and Phrases

Almost every website in our sample (85%) included the term “quality of life” somewhere in their palliative care content. The other two recommended phrases (“living with a serious illness” and “person/people with a serious illness”), however, each appeared on fewer than 20% of the websites. While these two phrases have yet to undergo user testing, they do adhere to recommendations for person-centered language emphasizing the person before the disease. These terms also speak to the palliative care patient as someone living with a disease, rather than dying from it. Using this type of language could have the dual benefit of conforming to person-centered recommendations, as well as describing palliative care as something that is pertinent to serious, not explicitly terminal, illness.

If you look at word use broken down by the type of organization, “quality of life” was used most often by hospitals (94%) and least often by hospices (75%). Use of “living with a serious illness” ranged from 19% of hospitals and hospices to only 6% of other community organizations, but “people or person with a serious illness” was used 13% of the time by all organization types.

How We Can Stay on Message as a Field

This analysis shows us that we see progress at trying to stay on message as a field. However, reframing palliative care is not an easy task. To help, CAPC offers bi-monthly Virtual Office Hours with expert marketing faculty as well as a robust Marketing and Messaging Palliative Care toolkit that contains numerous resources ranging from audience research and on-demand webinars, to image and photography guidelines, and more. Most recently, CAPC hosted a webinar to discuss the steps clinicians can take to positively influence public perception of palliative care.

As with all skills, staying on message takes practice, discipline, and effort. Remember, oncology, neurology, nephrology, and other subspecialties don't define themselves or even imply that they exist to treat people nearing the end of life—even though much of the time that’s exactly what they are doing. Neither should the field of palliative care.

The authors would like to thank Emily Franzosa, DrPH, for her guidance during the qualitative analysis.

CAPC's Marketing and Messaging Palliative Care toolkit contains additional resources on messaging, image guidelines, and more.

Get Started