Nourish the Roots: The Importance of Palliative Care Education in Medical School

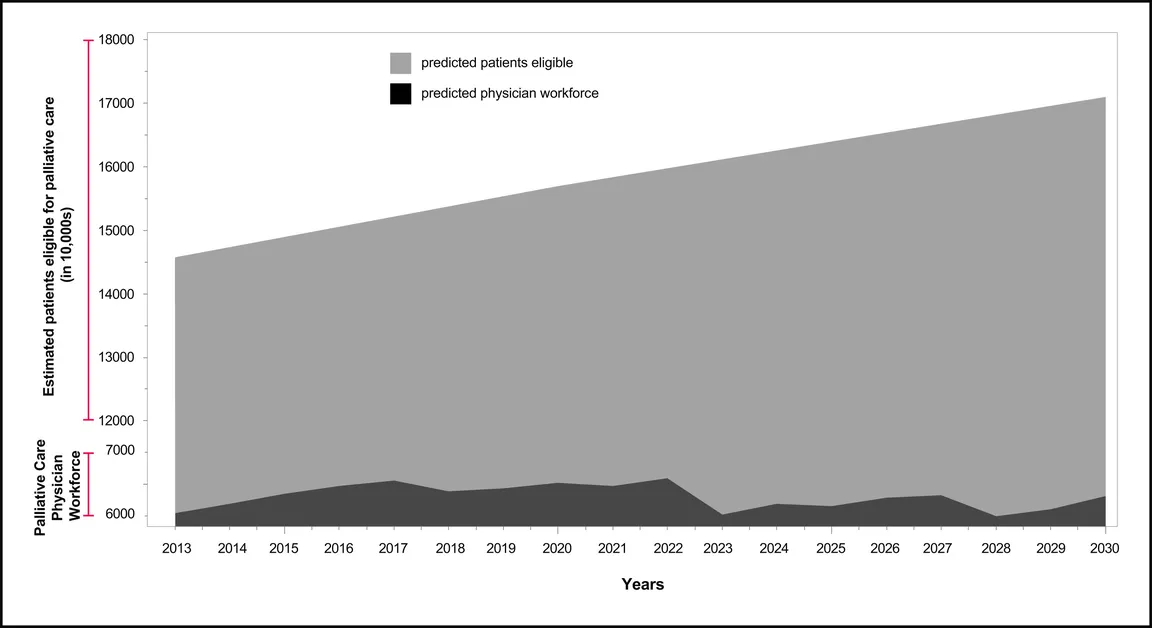

This graph should alarm you. With limited fellowship positions (355), an annual 3% loss of palliative care physicians due to burnout, a wave of current palliative care providers due for retirement, and our aging baby boomer population, there is a pressing need for more palliative care physicians. This need is so great we will not feasibly be able to meet it with our current palliative training structure.

This is not to say that progress in the form of the Palliative Care and Hospice Education and Training Act (PCHETA) and increasing available fellowship positions has not been essential. Unfortunately, it is likely not enough. Given this insurmountable workforce shortage, the most promising solution is to introduce palliative medicine into the medical school curriculum, so that future physicians of all specialties begin their careers with a strong grounding in the essential competencies of quality of care during serious illness. These include communication and shared decision making skills, pain and symptom management, and recognition of the need to support family caregivers.

The most promising solution is to introduce palliative medicine into the medical school curriculum, so that future physicians of all specialties begin their careers with a strong grounding in the essential competencies of quality of care during serious illness.

While a medical school graduate with palliative care training will not be able to provide the same level of specialized care as someone who has undergone specialist level fellowship training, their ability to handle goals of care discussions, pain and symptom management, and to better understand when to consult a palliative service will reduce the workload currently practicing palliative care teams face.

Not All Curricula Are Created Equal

A search of the current literature reveals many articles about medical school curricula and residency programs improving access to palliative care for early learners, but closer examination shows many of these programs fail to differentiate palliative medicine from hospice. In many cases, the only exposure many early learners get to palliative medicine is through a required hospice rotation or mandatory "end-of-life” training. While gaining hospice experience is inarguably valuable for anyone entering the medical field, leaving out the palliative care piece is a disservice to learners, patients, their families and other caregivers, and the health system and society as a whole.

In many cases, the only exposure many early learners get to palliative medicine is through a required hospice rotation or mandatory "end-of-life” training.

One study, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, showed that “palliative care referral for heart failure patients may be suboptimal due to limited provider knowledge and misperceptions of palliative care as a service reserved for those near death.” When a medical student or resident’s only experience with palliative medicine is centered around end-of-life care, it is easy to see why there is still so much confusion about the difference between hospice and palliative medicine, amongst both patients and physicians. As our population ages and more people live with chronic diseases, it is crucial that the next generation of physicians is adept at addressing the unique needs of people living with serious illness. Every future physician, regardless of their intended specialty, would benefit from increased exposure to palliative medicine.

Every future physician, regardless of their intended specialty, would benefit from increased exposure to palliative medicine.

Limiting palliative care education to the realm of end of life issues prevents future physicians from understanding the vast spectrum of care that falls under the palliative umbrella. It is a missed opportunity to incorporate lessons on pain management, how to lead a goals of care discussion, and methods of enhancing quality of life for patients with chronic illness and high symptom burden. This results in specialists seeing a patient with multiple comorbidities and poorly controlled chronic illnesses, and not referring that patient for palliative care consultation until their disease has reached hospice eligibility.

A study by the VA, published in the Journal of Palliative Medicine, found that patients received a palliative consult on average 38 days before death. One study surveyed cardiologists, sending them various scenarios to evaluate how these hypothetical patients might be managed. This study found that fewer than 50% of the 614 cardiologists who participated would discuss palliative care in two cases of elderly patients with late stage heart failure. This raises the question – if these cardiologists had more access to palliative training early on in their medical education, how different would these results be?

A Recipe for Change

While improving palliative education at the medical student and resident level may seem an obvious solution to this issue, it is not easily implemented. Curricular reform is notoriously difficult, and the field of palliative medicine has been unable to compete with other specialties for a four week block. The most effective palliative care educational experiences are offered longitudinally across multiple years of medical school and residency. Importantly, medical students want additional training in symptom management, legal and medical ethics, and palliative care. One study found many students have significant anxiety surrounding caring for patients with needs they have not been adequately trained to address. However, educating future physicians requires faculty stakeholders who are trained in palliative medicine and compensated as educators to rise to the task of ensuring curricular gaps are filled.

As palliative care clinicians, we understand better than anyone else the importance of an upstream intervention – why should palliative care education be any different?

Very few medical schools have dedicated palliative medicine educators, and most teams are overwhelmed with clinical service demands. Implementing student interest groups, ensuring students have valuable clinical and educational experiences in palliative medicine (not just hospice), and continuing to fight for funding to increase access to palliative care education are all imperative pieces of this complicated puzzle.

As palliative care clinicians, we understand better than anyone else the importance of an upstream intervention – why should palliative care education be any different?

__________________________________________________________________________________

Kayla is a former hospice volunteer, pain researcher, and bedside singer currently in her fourth year of medical school at California Northstate University. She is currently applying to Family Medicine residencies, and plans to pursue a Hospice and Palliative Medicine fellowship after residency.