Implicit Bias and Its Impact on Palliative Care (Part Two)

In part two of this interview with Kimberly Curseen, MD, we continue our discussion of implicit bias in palliative care from part one.

CAPC: Previously, we discussed implicit bias and its potential impact on palliative care. What are different ways to reduce the harmful consequences of this human condition? You’ve spoken about mindfulness training as a tool for overcoming it. But what do you do when you don’t have time to, in your words, “get your mind right and fix your face?”

Dr. Curseen: Mindfulness is one very useful tool. I call it the mental state achieved by focusing on one’s own awareness and being present in the moment. When you’re mindful, you can allow yourself to inventory and examine your own feelings, thoughts, bodily sensations. Once we become consciously aware of what we are feeling, we can make a choice about whether or not to act on that.

When you’re a palliative care physician, you fill up your toolbox with how to manage medications, and appropriate phrases for communication, and all of these logistical things. I believe that being mindful and developing skill in mindfulness as a technique will not only help us communicate with our patients better, but also sustain us in this work. It allows you, in those few moments, to really figure out what it is that’s happening.

When I train residents or students, I say, “You look mad.” To which they reply, “I’m not mad,” and I answer, “Well, you look uncomfortable.” They respond, “I’m upset, I’m uncomfortable.” So I ask, “What are you upset about? You can’t be mad with the patient, because you haven’t met them yet.” They acknowledge that’s true.

Then we can talk about what’s really happening. “Let’s sit down and think about it for a minute” Now they’re sitting there calmly and we’ve named the emotions. Then I say, “Just think about it silently for a minute and get your words together.” That’s my way of getting them not to talk but really to think consciously about what their feelings and thoughts are so that they can do what’s best for the patient and not act out our unconscious feelings when we meet the patient.

Because I ask the trainees to name their own feelings in a non-judgmental way, they’re able to answer honestly, in a safe space, “Well, look. This person is a drug addict, they’ve hurt people, they’ve been in prison, and I just think that’s terrible, and it’s not right.”

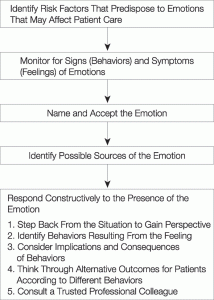

My response, “So how will you approach this person that we have to see? What is it that you need to be able to do to fulfill your professional responsibilities to your patient?” It’s a way to get down to the root and allows the few moments necessary for the person to become self-aware. Clinicians need to learn to notice their feelings, not because there is anything wrong with having feelings, but because we should be in control of whether or not those feelings are influencing how we care for our patients. Stop for a minute once the emotion occurs, to ask oneself these questions: What are my feelings? Why am I feeling that?

And it is also worth becoming very aware of one’s body and body language. Sitting in a chair, for example, I could take stock of my body language. Are my shoulders tensed? Are my arms and legs crossed, signaling that I am uncomfortable being there and wish I could leave? How am I holding my face? Am I tight, are my eyebrows raised? Or is my face relaxed and smiling? Do I have open body language? Then start to relax those things even before I engage the patient.

CAPC: You mentioned self-awareness and you’ve spoken about personal versus normative standards. Please elaborate on that.

Dr. Curseen: There was a study in which two groups of medical students were exposed to inappropriate behavior, or what we would consider non-politically correct behavior. Then one group was asked, “What should a good doctor do?” The other group was asked to reflect on their own personal standards, and to do a more of a deep dive on “How does that make you feel? What are your own personal standards? What do you think about the situations?”

The first group, when asked “What should a good doctor do?” answered as they knew they were supposed to: “I’m supposed to treat all patients with pain the same, even though they have a history of heroin addiction, and ask them what their pain is on a one to five scale.” This leads to resentment, because we have already unintentionally implied that their own implicit biases are not consistent with medical professionalism. It feels like there’s a judgment being placed. In other words, I know how I really feel, but I also know you want a different answer, so that is what I’ll give you.

The other group of students were given the same case example, but asked to reflect on it and how it makes them feel. We get answers like, “Well, yes, this person’s a drug addict. I have a hard time with that, but maybe they have “real” pain and I’m not quite sure how to balance that. I think that if I were facing that situation, I might react negatively. There’s probably a better way to do it, but I just don’t know.”

In this scenario, rather than asking them to pass judgment on the hypothetical colleagues’ reluctance to provide pain medicine, you’re asking them to name these contradictory feelings out loud, so they can make conscious decisions. “You’re faced with this difficult situation, how are you going to manage that?”

That requires becoming aware, first, that the situation brings up negative or judgmental feelings about the patient- understandable feelings, but feelings that should not determine what is medically most appropriate for the patient. The key questions are: What am I feeling? Are these feelings something that should determine how I treat my patient? Is there a different way?

Or you can say, “You were able to talk about hopes and fears with this patient and family; what made you not able to have that conversation with this other patient and family? What do you think might happen if you tried?” Then you allow them to think about that, and it’ll come out “I wasn’t sure, and, I was afraid they would be hostile to the discussion. How could I have gone in there to this family and made this work?”

This way, the learners had permission to inventory their feelings as a normal part of clinical practice, recognize their own biases, and identify solutions to fix it. Normalizing naming of, and discussion about, feelings eliminates the sense that the clinician is being judged. There is a lot less resentment and growing awareness of the necessity of being a reflective practitioner in healthcare.

There’s a lot more talk about how to identify implicit bias, than there is to how to make it better now that we’ve identified it, so that it does not unconsciously harm our care of our patients.

CAPC: You have also mentioned the Implicit Association Test (IAT) and other tests meant to increase self-awareness. How do those get used in medical school training, or in any medical training? Where do you access them?

Dr. Curseen: There’s no standard for incorporating this in medical training. They do get used in corporate America—usually in diversity training. The trainee is asked a series of questions to help him or her become aware of what the biases are, and then they participate in some workshops to build awareness usable in everyday life.

It needs to be done in a space that’s safe, which allows people to know that it is 100% normal and universal to have implicit bias. It allows people to express how they feel in a place that normalizes identifying and talking about feelings that is not judgmental.

There’s a lot more talk about how to identify implicit bias, than there is to how to make it better now that we’ve identified it, so that it does not unconsciously harm our care of our patients.

CAPC: Another tool you have previously mentioned, “other race” training, is focused on ways to see the other as an individual.

Dr. Curseen: Yes. There is an “other race” effect in implicit bias. In one study Caucasian participants were exposed to different people who have traditional African-American features.

The first time the participants looked at the photos, everybody looks the same, because our brain files things in categories. But repeated exposure to the same African-American faces enabled them to make distinctions between the individuals. So, they no longer were “black people”, they became, instead, Subject #1, and Subject #2. Once they were able to make the distinctions between individuals, they found a correlation with a decrease in racial bias. This demonstrates that our biases—even though we all have implicit biases—can be modified, and our actions can be modified with training.

CAPC: You earlier mentioned the possibility of misinterpreting signals. Can you talk a bit more about perspective taking?

Dr. Curseen: We want students to develop empathy.

Perspective taking is the cognitive part of being empathetic, and the ability for us to really see from another person’s perspective. Remember—when you first meet somebody, you’re writing an unconscious narrative, you’re writing a story. Then we start attributing motives, again unconsciously, to the narrative we have created. Once that happens—our expectations for the other person’s behavior are formed and our behavior tends to become self-fulfilling. The other person realizes we don’t trust or respect them and begins to behave accordingly.

When you’re spending time taking perspectives, you stop at, “I’m in a room with somebody and I’m having all these thoughts. Let me find out more about this person, this family” Once you have identified and named these thoughts, then you can decide whether these feelings are going to help you to care for your patient, or not. Conscious naming of what we are feeling allows us to return to professional behavior. In palliative care that means sitting down with the patient and asking them “How can I best take care of you?” What are your hopes? What are you most concerned about?”

Then, I’m also making clear that I’m the palliative care clinician here, and my hope is to help you feel better, I’m here to help you make decisions that are best for you, to advocate for you. So, I’m actually putting my intentions out there in a clear manner, on the table.

Then when I see you have different reactions to the things I’m saying, I name the emotions I’m seeing. “I see that you’re sad, I just said the cancer has come back, what are you feeling now?” I’m going deeper to get your perspective, going right to the source.

Through this conversation, I’m learning more about who this patient is as a person. How can I modify a treatment plan or my recommendations to really fit their perspective and their priorities?

If you practice perspective taking it allows for examination of the differential diagnosis of a difficult interaction, it allows you to sit back and think, okay, what might that person be thinking about or remembering or fearful about?

Then, spending some time thinking about, if I was in that same situation as my patient, how would I have reacted? Is there another way to think about it? If I’m defensive, then I can’t listen or hear anything. I can’t give the relationship a full chance if I can’t let go of the swirl of emotions that I’m feeling for a few minutes, to make sure that what I’m seeing is actually what I’m seeing.

If we truly believe that care is a basic human right, then we must provide it to everyone no matter who we think they are, and no matter what they think about us.

It helps to be very deliberate about how you run a family meeting or a conversation about serious news with a patient. Learn the empathetic statements and the body language, and incorporate that as second skin into your natural practice routine. This helps us to deliver care consistently and with less disparity. When we do something by habit and rote, despite our implicit bias, we improve the reliability of our care. Our family meeting and our communication is our procedure, so we’ve got to do the procedure professionally and consistently and well.

Finally, we practice palliative care. Period. Not palliative care for super-awesome people who think like us. Not palliative care for the nice or the kind or the deserving. This service, what we’re doing here in palliative care is practicing mercy. At the end of the day, simply because you are a human being, you get to experience this care. If we truly believe that care is a basic human right, then we must provide it to everyone no matter who we think they are, and no matter what they think about us.

They get to be their best selves with us, and we get the privilege of caring for them. It’s easy to do this job when patients and families love you, it is hard to do it when they don’t. But we’ve got to do it well, no matter what the circumstances. Everybody comes to us clean – a fellow human being in pain. “Be kind. Everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle.” (unknown)

Oath of Maimonides

“The eternal providence has appointed me to watch over the life and health of Thy creatures. … May I never see in the patient anything but a fellow creature in pain.”

To meet and network with other leaders in the field and continue the discussion regarding palliative care, please join us at CAPC National Seminar 2019 and Pre-Seminar Boot Camp.