The Invisible Millions: Caring for Latino Patients and Families during COVID-19

This blog post rounds out a three-part series on health care disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic. The first post explores ways in which health disparities for Black/African American persons have been exposed and exacerbated during this time. The second post discusses the pandemic’s impact on American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN)/Native American populations.

Introduction

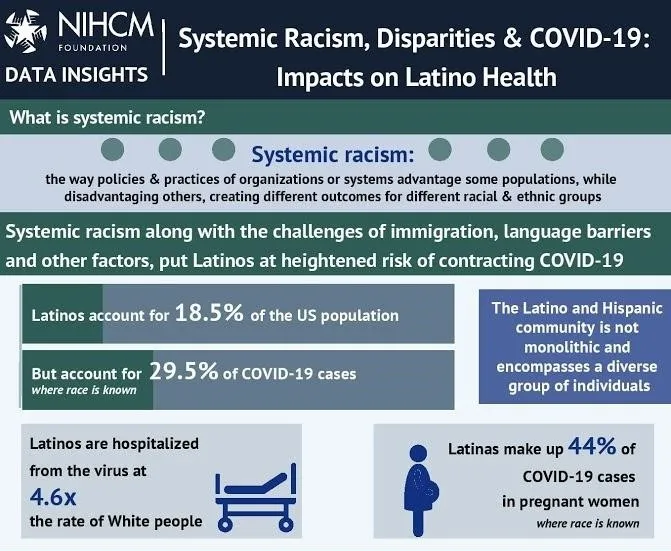

As we approach the one-year anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Latinos – also referred to as Hispanic or Latinx populations – remain among the hardest hit. Since some of the earliest outbreaks in food production workplaces, Latinos have comprised 33% of COVID-19 cases as of December 2020 (despite accounting for 18.5% of the population); been hospitalized at 4x the rate of White Americans; and experienced greater case outbreak severity and death rates in nursing homes. There is also a good chance that these figures under-represent the vast impact of COVID-19 on Latino communities, due to a persistent lack of complete and accurate data.

As with Black and American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations, there are numerous reasons for this disproportionate impact, ranging from health-related factors (e.g., higher rates of underlying health conditions such as diabetes and obesity, higher uninsurance rates, less access to health care), to economic factors (e.g., overrepresentation in low-wage and/or essential jobs that do not allow for remote work), to social factors (e.g., higher chance of living in multigenerational homes, lower levels of trust in government, language barriers). These have all been compounded by early failures in COVID-19 testing within Latino communities, which allowed for the infection to rapidly spread.

Similar to other populations, palliative care teams have played an important role for Latino patients (and their families) living with a serious illness during the pandemic. They have provided personalized care, which has allowed for learning of hopes, top worries, and concerns—ultimately matching care to those needs and priorities.

Key Background on Latino Populations

There are a couple of broad considerations that health care providers should keep in mind as they work to provide culturally competent/responsive care for Latinos.

Diversity

First is the diversity of the roughly 60 million Latinos living in the U.S., with origins in dozens of countries, including Mexico, Spain, Cuba, Honduras, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, and many more. Latinos are not a monolith – there is tremendous heterogeneity in terms of language, educational attainment, socioeconomic status, spiritual practices, and culture – all of which can impact both access to care and care preferences.

Latinos are not a monolith – there is tremendous heterogeneity in terms of language, educational attainment, socioeconomic status, spiritual practices, and culture – all of which can impact both access to care and care preferences.

Barriers to Care

Second is the unique barriers confronting undocumented persons, which comprise roughly 10% of the Latino population in the U.S. These barriers include everything described in the previous section, but to even greater degrees. For instance, only 34% of undocumented immigrant adults rated themselves as proficient in English; and although this percentage has grown over time, it can still complicate communication with clinicians.

Lack of Benefits

Because of their status, undocumented immigrants are more likely to be employed in “under-the-table” jobs that do not have benefits such as health insurance or paid sick leave, contributing to higher rates of poverty and creating economic pressure to continue working, even if sick in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. They are less likely to have health insurance, and more likely to seek out care in community health centers which can be under-resourced and less likely to provide specialty services (including palliative care). And, unique to undocumented persons is the fear of interacting with organizations or institutions that could expose their status and risk deportation, including schools, hospitals, clinics, and government entities of any type.

Systemic Racism

A key problem is the United States' long history of systemic racism that puts Latinos – citizens, legal immigrants, and undocumented persons alike – at higher risk of negative health outcomes. Much has been written about societal conditions borne out of this racism, but a recent policy example reinforces the point: the Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds Final Rule (“Public Charge rule”). In immigration law, the term “public charge” refers to whether an immigrant is likely to become dependent on government assistance, either now or in the future. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) can deny an application for legal entry into the U.S. or to become a lawful permanent resident if it determines that the individual is likely to become dependent on the government (i.e., a public charge). Historically, DHS could use factors such as an individual’s age, health, income, family size, education, and skills to make these determinations. It could also consider whether the individual received benefits such as public cash assistance or placement in long-term care at the government’s expense; however, it did not consider the use of health care, housing, or nutrition benefits.

"A key problem is the United States' long history of systemic racism that puts Latinos – citizens, legal immigrants, and undocumented persons alike – at higher risk of negative health outcomes."

The new Public Charge rule, which went into effect on February 24, 2020, expanded the list of public benefits that the DHS could use to deny an individual’s application for admission to the U.S. or adjustment of legal status. These new benefits include the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid for non-pregnant adults, and public housing – all of which have been a critical part of the safety net in COVID-19. While the rule does not apply to all immigrants and continues to face multiple legal challenges, it has created significant fear and confusion across immigrant communities – a significant percentage of which (44%) have Hispanic or Latino origin. Many have stopped accepting government assistance regardless of their eligibility, including an estimated 260,000 children who have been disenrolled from programs like Medicaid and SNAP, and are instead visiting food pantries and forgoing medical care. Realizing the response to the Public Charge rule could hinder pandemic response efforts, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services clarified that COVID-19-related testing and treatment would not be one of the factors considered in applications for a change in legal status; however, it is almost certain that the chilling effect of this rule contributed to the disproportionate impact of COVID in Latino communities.

While events throughout 2020 have elevated awareness of systemic racism and inspired commitments to address injustices in health care and beyond, this work will continue to be undermined by many racist policies, like the public charge rule, for years to come. Hunger, missed preventive health services, avoidance of health care when sick, and other dropped benefits will extend and amplify the cycle of disparities for many Latinos and other affected immigrant communities.

Palliative Care for Latino Patients with Serious Illness

COVID-19 infection and its aftereffects represent a new form of serious illness affecting a disproportionate number of Latinos. However, the number of Latinos living with serious illnesses such as cancer, advanced heart failure, end-stage liver disease, end-stage renal disease, and advanced neurologic disease, among others, has not diminished simply because medical attention has focused on the pandemic. In fact, individuals needing serious illness care may have postponed or avoided care due to immigration concerns (i.e., being discovered as undocumented, or being denied legal residency as a result of accessing services); financial constraints, as Latinos were also disproportionately impacted by the economic downturn early in the pandemic; and/or the fact that many hospital systems curtailed non-essential services to prevent the spread of infection.

As palliative care clinicians care for Latinos in these heightened circumstances, here are some culturally relevant considerations for care:

Familismo

Familismo is the central role of the family and relationships therein. Every patient should be treated as an individual and their own priorities, hopes, wishes, and concerns should be explored. That said, Latino patients and families frequently make decisions as a family unit, and sometimes patients will make choices that prioritize the family unit’s preferences rather than their own individual preferences. For instance, they may choose to value prevention of suffering for the family unit above the prevention of their own individual suffering (which may be difficult to understand or uncomfortable for a healthcare provider).

Individual palliative care providers should ask patients who helps them make decisions, and also involve and build trust with family members (or whoever is in their close support system) in care planning discussions—unless the patient expresses clear opposition to this. This will allow the family to express their honest views of the medical care provided to their loved one, and the service provider can support these discussions.

Individual palliative care providers should ask patients who helps them make decisions, and also involve and build trust with family members in care planning discussions [...]

La espiritualidad

Many Latino patients also rely on faith and la espiritualidad (spirituality) as an important way of coping with serious illness. During the pandemic, family members of patients with critical illness due to COVID-19 would sometimes express hope for a miracle, for their loved one to recover from the illness. Through Western clinical lenses, this expression of spiritual coping might be perceived as the family being “in denial” about the severity of the patient’s illness, which could prompt a team to consult palliative care.

Palliative care clinicians can help by providing supportive listening and by involving spiritual care support, ideally Spanish-speaking or from the patient’s own faith community, as part of the interdisciplinary palliative care team. Research has shown that involving a spiritual care provider from the hospital (compared with relying on a community-based spiritual care provider) is associated with higher rates of hospice use and fewer ICU deaths.

Palliative care clinicians can help by providing supportive listening and by involving spiritual care support, ideally Spanish-speaking or from the patient’s own faith community, as part of the interdisciplinary palliative care team.

Dignity

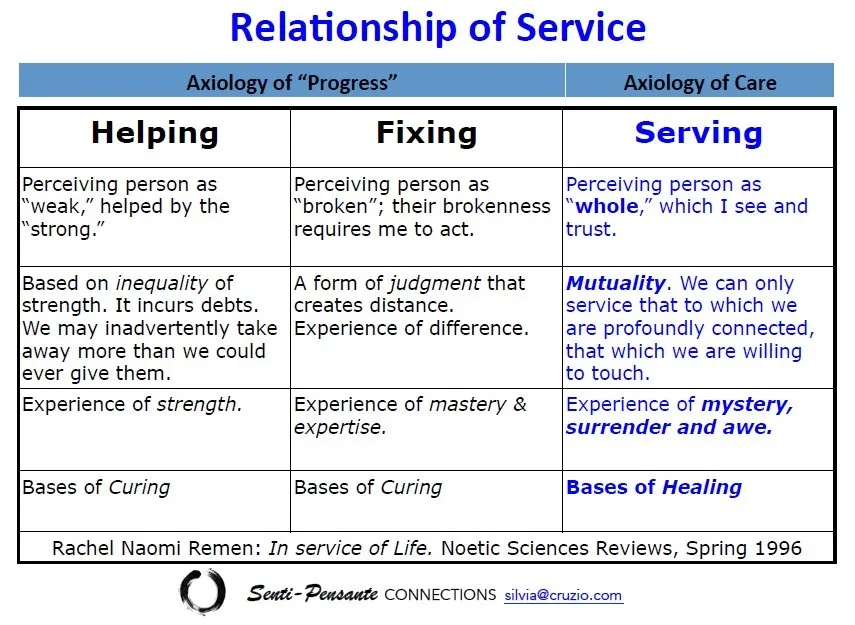

Given the power imbalances that often occur in the patient-provider relationship, it is important to remember to ground interactions in cultural humility. This requires remembering that each team member is the expert of their own domain, and that the team includes the patient and family. The framework of Helping, Fixing, or Serving can be a helpful reminder for how to center the patient.

Promotores de Salud

Promotores de Salud, or community health workers (CHWs), are “trusted member[s] of the community who empower their peers through education and connections to health and social resources.” They can play an invaluable role in educating Latino patients on what palliative care is (since misconceptions persist) and where to find it, and they should be included as part of the palliative care team. Familias en Acción, with support from the Cambia Health Foundation, developed a curriculum, “Empodérate” in both Spanish and English that helps promotores and other care navigators empower patients and families to ask for palliative care.

[Promotores de Salud] can play an invaluable role in educating Latino patients on what palliative care is (since misconceptions persist) and where to find it, and they should be included as part of the palliative care team.

Teams can support promotores’ efforts by working together to develop Spanish-language materials about their programs and services; sometimes, institutional media or marketing departments can assist with this work.

It is important to note that, as essential as promotores de salud are, they are also at higher risk for COVID-19, since – by definition – they reside in, work with, and are part of vulnerable communities. Part of incorporating CHWs into the palliative care team means ensuring that these health care professionals are afforded the same protections (particularly with regards to PPE) as providers in acute care settings.

Use of Medical Interpreters

There is a big difference between promotores de salud, who often function as advocates, explainers, and/or cultural interpreters, and medical interpreters, who help translate health care discussions into the primary language of the patient.

The National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th edition, specify that palliative care teams should use qualified medical interpreter services, either in person or via telephone or video. This is particularly critical when having discussions on goals and preferences for those diagnosed/hospitalized with COVID-19 and generally for care requiring decisions about treatment for any serious illness as well as at the end of life. Additional guidance on the use of interpreters in palliative care can be found here.

The National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th edition, specify that palliative care teams should use qualified medical interpreter services, either in person or via telephone or video.

Unpacking and Dismantling Racism and Discrimination

Patients, families, promotores de salud, and others have reported encounters in which clinicians exhibited racist behavior. Examples included making disparaging remarks about insurance (regardless of whether the patient was insured); failing to engage patients and/or making them feel invisible, unintelligent, or like a burden; pressuring patients and families to make decisions aligned with the clinician’s preference; and, in rare instances, refusing to treat based on immigration status. Such actions are racist and unacceptable. Palliative care teams must hold each other accountable, and be prepared to speak out if they observe these or other racist actions and/or microaggressions.

As our population’s demographics change, the need for culturally competent palliative care for Latino patients and families is growing. It is increasingly important for palliative care clinicians to become comfortable with engaging and listening to Latino patients and families, especially with respect to fears of deportation; cultural and spiritual context of illness understanding; and care concerns in order to provide effective and compassionate care throughout a serious illness.

Additional Resources

For more information, we encourage you to review the resources below.

- Bridging Language Barriers During the COVID-19 Pandemic, a special recognition poster accepted to CAPC 2X4. Click here to watch a recording of the poster presentation.

- Exploring the Perspectives of Oncology Hispanic Population at End-of-Life in an Inpatient Hospital Setting, a poster accepted to CAPC 2X4

- Familias en Acción's publication, Education for Building Culturally Skilled Health Professionals and Community Health Empowerment: Resources to improve access to palliative care for Latinos

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the following people who contributed their expertise and reflections to inform the writing of this blog:

- Silvia Austerlic, MA, Intercultural Facilitator and Consultant, Senti-Pensante Connections (www.senti-pensante.com)

- Marie Dahlstrom, MA, Co-Host, Abuelas en Acción: A Podcast for Our Common Good. Founding Executive Director of Familias en Acción, Portland, Oregon (https://www.familiasenaccion.org/podcasts-2/)

- David Hui, MD, MSc, Associate Professor, Department of Palliative Care, Rehabilitation and Integrative Medicine, Department of General Oncology, MD Anderson Cancer Center

Themes from Recent CAPC Blogs on Addressing Health Disparities in COVID

While reflecting on the three most recent CAPC blogs exploring the care of Black, American Indian and Alaska Natives, and Latinos during COVID-19, we have identified a few themes below:

1. Telehealth may exacerbate health disparities

First, an unexpected benefit of the pandemic has been a reduction in regulatory barriers, enabling rapid innovation in care delivery – particularly in telehealth. Early on, however, some advocates identified the possibility that telehealth might exacerbate health disparities due to factors such as inability to afford technology, lack of broadband access, digital literacy, or privacy concerns. One physician shared a story about a Spanish-speaking patient who had indeed slipped through the cracks in a virtual care environment. And early data suggest that Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients are using telehealth at much lower rates than White patients. While it is too early to draw any final conclusions about the relative merits of telehealth for underserved populations, all providers (including palliative care teams) must be thoughtful about how they deploy this technology and strive to meet patients “where they are.”

2. More research needed on access to high-quality palliative care

Second, more research and evidence are needed across all three of these populations (and other underserved racial groups) to ensure high-quality palliative care for all patients living with serious illness. There remains a paucity of data and information on the number of people receiving this specialty care, perceptions of and experiences with palliative care, patient outcomes, techniques to guide palliative care interactions in unique populations, etc. CAPC is committed to addressing these gaps by pursuing work to better understand both barriers that impede and facilitators that promote equitable access to high quality palliative care. We also encourage other palliative care researchers to pursue studies to examine differences in utilization and quality of palliative care for unique populations.

3. Relying on research may lead to assumptions, reinforcing cultural biases

There are no easy answers. As much as we would love to provide a checklist that could ensure perfectly culturally competent care delivery, no such thing exists. Every population has a unique history that can be helpful for providers to know; however, relying on racial and ethnic background research too heavily runs a serious risk of making assumptions that may or may not apply to the individual in front of you and reinforcing cultural biases that could negatively impact care. To that end, it can often be more fruitful to learn about each patient as an individual and to ask them about disease understanding, beliefs, and their (or their families’) approach to decision-making. Asking people what has happened to them in the past through a trauma-informed care lens will also provide insight into the patient and family backstory, thus increasing understanding of present day fears, beliefs, and behaviors.

4. Providing culturally competent care means self-reflection by providers

Working towards delivering more culturally competent care requires providers to engage in continuous, rigorous self-reflection that will enable them to identify and remove biases. White health care professionals in particular must continue to research and reflect on the harm they and their institutions have caused to Black, Latino, and American Indian/Alaska Native communities, and seek opportunities to correct these injustices. This may include some discomfort. If the prospect is too disturbing or scary, we recommend looking into work on White fragility; it is our experience that this can be helpful preparation for hearing hard truths, taking risks, getting things wrong, accepting feedback without defensiveness, and trying again. Establishing processes for team accountability can be helpful, since we all have blind spots. This work should include creating a culture of transparency and developing agreed-upon processes/language for (respectfully) calling each other out.

5. Diversity and representation needed on teams

Finally, while achieving greater diversity and representation in the health care workforce is important, this will take a concerted effort over many years, beginning with improving the pipeline to health professional training from underserved communities. Although it will be challenging, palliative care teams can increase the presence of minority providers who are part of the team-based model of care, including registered nurses, NPs, doulas, CHWs, etc. And, in the meantime, White providers must participate in continuous communication skills training programs that target emotion-handling and rapport-building behaviors. A 2014 study found that physicians’ positive emotional tone is associated with higher trust, particularly in the visits of African-American primary care patients. Ultimately, across populations, it is critical to create space for patients to speak and providers to listen.

Final Thoughts

This is why we believe that palliative care is uniquely well-suited for supporting improvements in health and health care equity. Ultimately, palliative care is not based in assumptions; its interprofessional approach recognizes the uniqueness of each individual and their needs and concerns – the social inequalities, psychological challenges, spiritual and religious implications, and the financial distress, along with the physical suffering – regardless of race. So we want thank you for all that you do to support people living with serious illness and their families. Your compassion and commitment is what sustains us during these difficult times and gives us hope for the future.

Be the first to read articles from the field (and beyond), access new resources, and register for upcoming events.

Subscribe